As a college student with an affinity for the arts, history, and community engagement, I jumped at the opportunity to do an educational field trip through the Southwest with SHSU’s Center for Law, Engagement, And Politics. Moreover, I was particularly excited when I learned that we would be stopping at the Old Jail Art Center (OJAC) as part of our learning adventure!

And what an adventure! Though relatively new to the art scene, I could recognize the breadth of OJAC’s collection. Before even entering the Museum’s interior, I immediately recognized and was thrilled to see three Jesus Moroles sculptures, all of which were more elaborate than those I have previously seen.

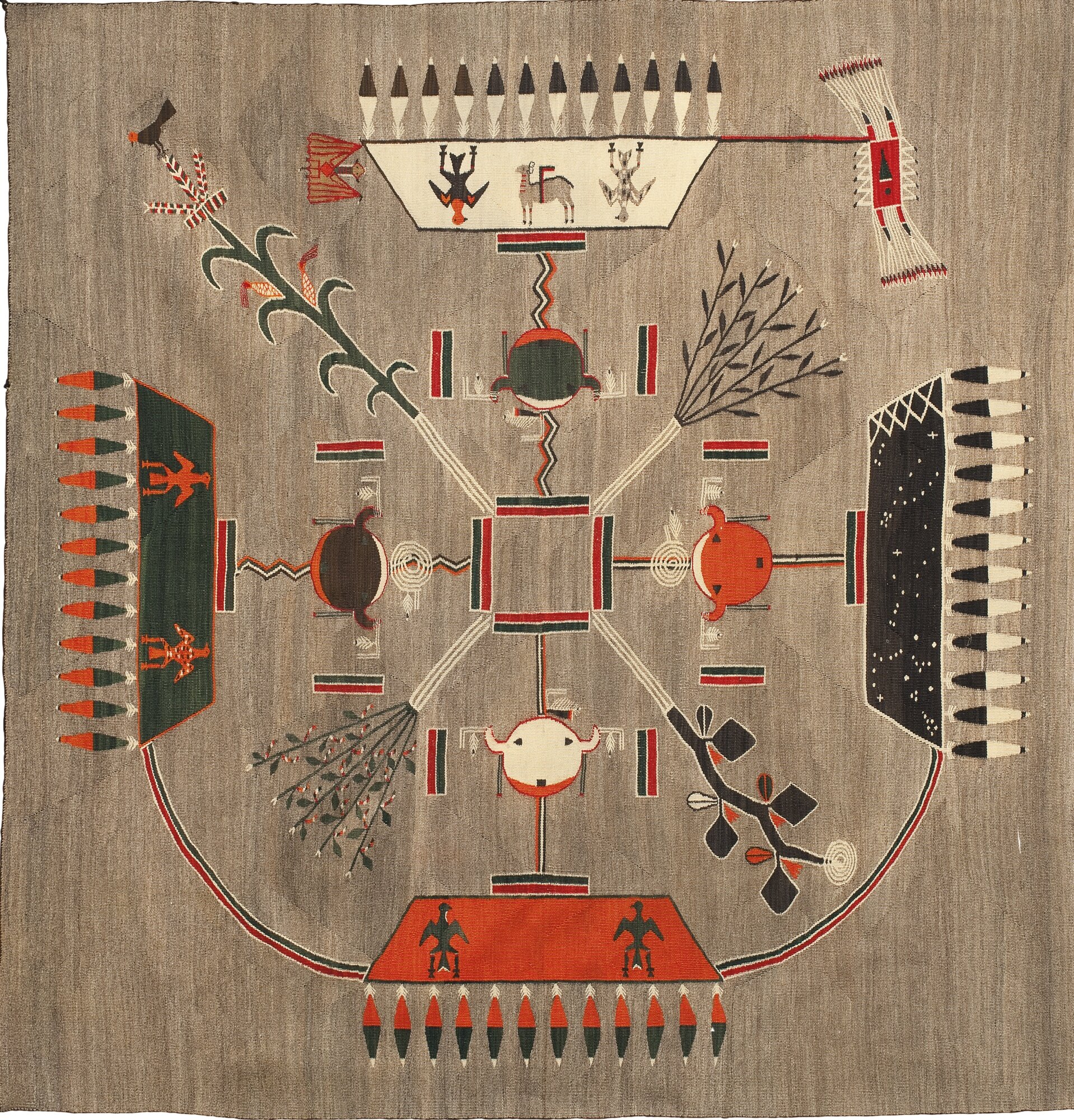

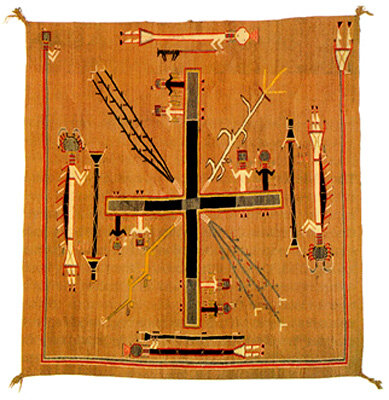

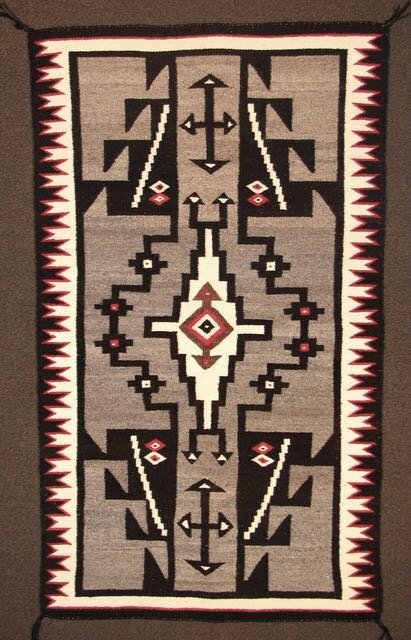

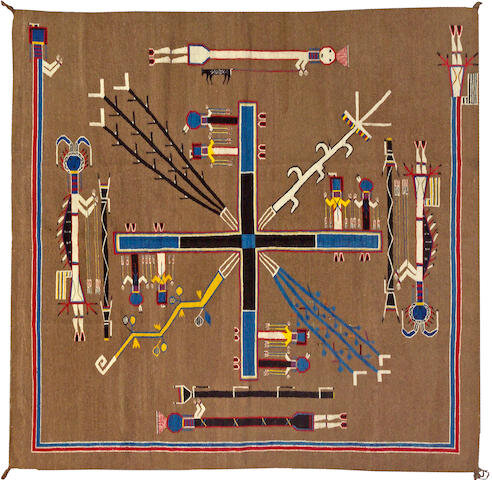

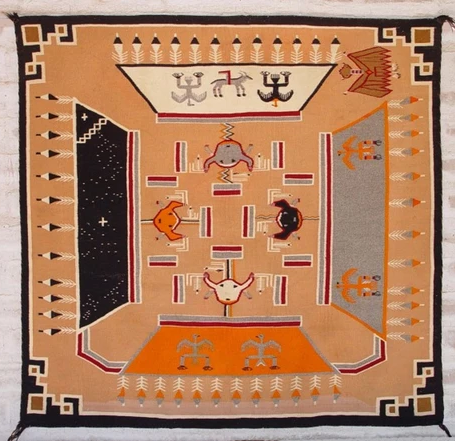

Although specializing in Texas art, OJAC’s collection is impressively eclectic. The museum has a diverse range of media, styles, and historical eras represented, from pre-Columbian, to John James Audubon, to Paul Klee, to Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, to members of the Fort Worth Circle.

There were several pieces that I was happy to see, including a few by James Surls—an SHSU graduate! I have had the chance to view his sculptures in other venues, but OJAC’s

I See Five was one of the most enthralling I have seen. Its spherical composition combined with Surls’ signature petals was by far my favorite piece of the Sam Houston State University’s day. Additionally, I enjoyed seeing some of his non-sculptural work, especially a piece titled, “On Being in her Mystery.”

I was also gratified to see works by new (to me) artists. I particularly liked Nature Morte aux Roses, by Henri Fantin Latour. In fact, this piece prompted me to research the artist, and I learned that his use of roses was a hallmark of his overall work.

The current exhibits were also impressive. Leigh Merrill’s Garden of Artificial Sugar and Karla Garcia’s When the Grass Stands Still both offered thought-provoking experiences, and the visual impact was complemented by the informative gallery guides, which include short interviews with the artists. This touch not only enriched my experience, but also helped me develop an appreciation for the art before me.

Another aspect of this visit that I thoroughly enjoyed was the historic nature of the building itself. The core of the Art Center is the county’s old jail building, which adds to the venue’s charm and character. And as a criminal justice major, I especially enjoyed the experience of entering a former jail cell to view Karla Garcia’s When the Grass Stands Still—perhaps the perfect juxtaposition of setting and subject matter.

This was my first time in Albany, Texas, and I greatly enjoyed the beauty provided by the OJAC in this corner of Texas. From its educational efforts in the larger community, to its vast collection of art, and to its friendly and knowledgeable staff, the OJAC adds to the Lone Star State’s cultural richness and to every visitor’s cultural development.

More than anything else, the Armory Show was about freedom: new ways of thinking and seeing, and individual expression. The show’s motto, "The New Spirit," was connected not just to changes in the visual arts, but also to social, cultural, and political transformations in the early part of the last century. The OJAC is proud to uphold this new spirit with representation of the following influential artists whose work was included in the original Armory Show.

Olivia Discon, Sam Houston State University Student

![Back in the Saddle! [History Trunks Ready to Travel!]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54de791be4b00f1b03108693/1757361380352-UNVWG66XK9ORGZFTSS0X/Traveling%2BTrunk%2BSquarespace.png)