The Navajo people are Native American tribe in the Southwestern United States. Most Navajo people now live in New Mexico and Arizona. Traditionally, the Navajo were largely hunters and gatherers. The tribe grew crops of corn, beans, and squash. When the Spanish arrived in the Americas, the Navajo began herding sheep and goats as a main source of trade and food, with meat becoming an essential component of the Navajo diet. Sheep became a form of currency and status symbol. The practice of spinning and weaving wool into blankets and clothing became (and remains today) an important part of Navajo economy and art.

The Navajo language is called Diné. Nearly 150,000 Navajo people speak Diné today, making it the most-spoken Native American language in the United States. In addition to an alphabet of letters, the Diné language includes symbols.

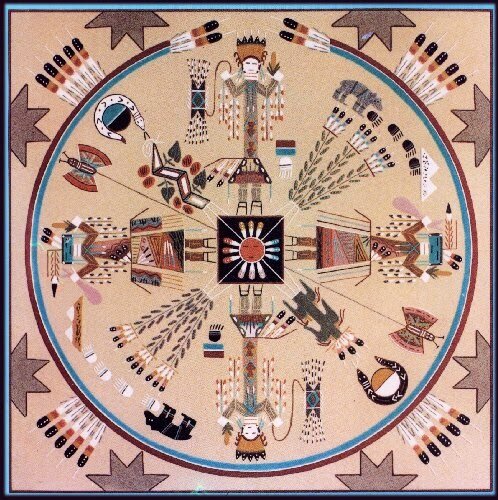

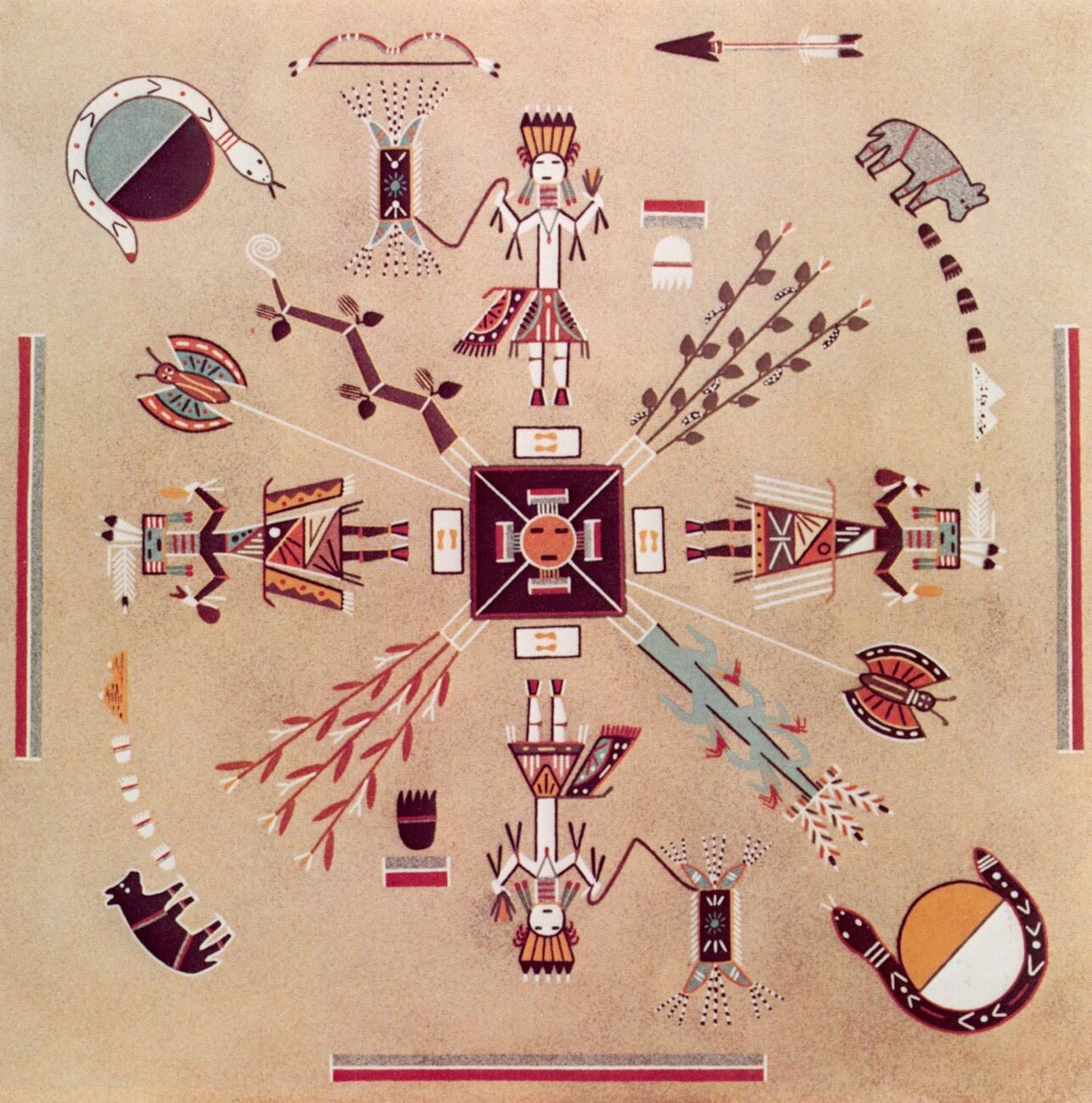

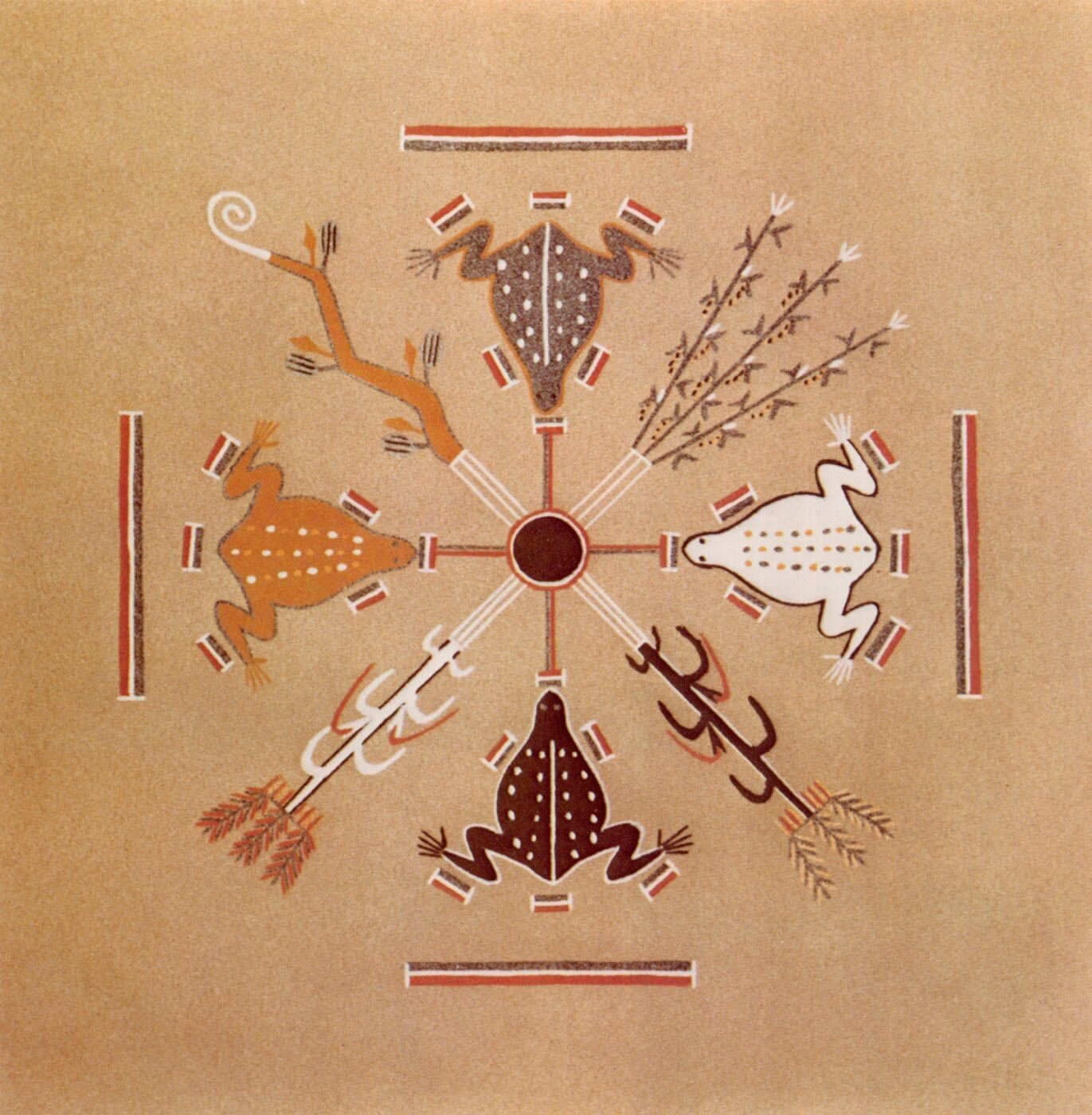

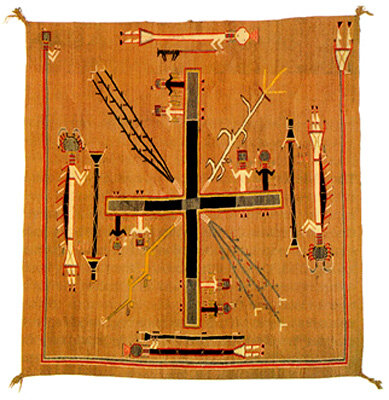

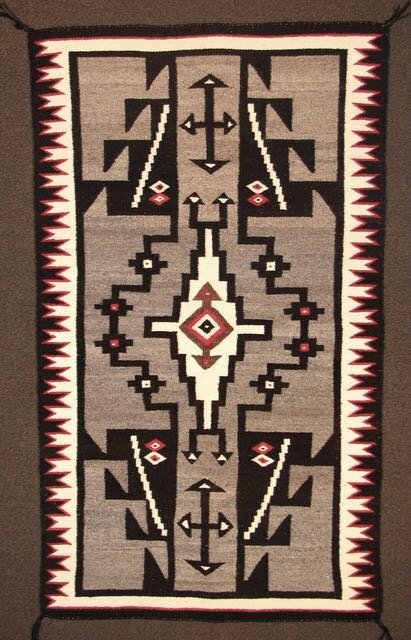

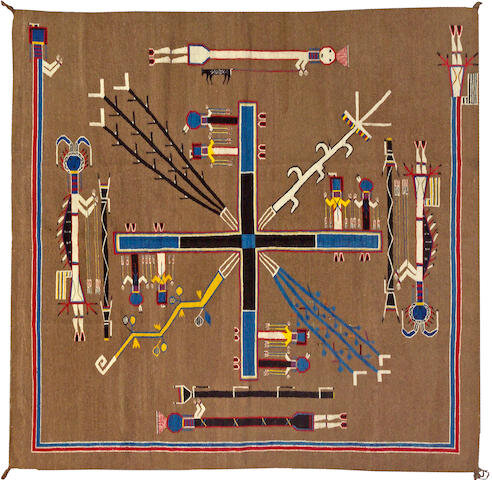

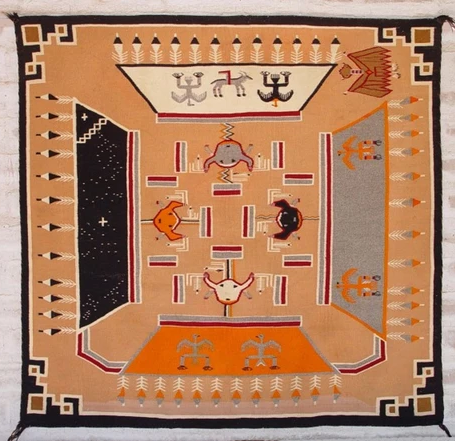

Some of the most important symbols in Navajo culture are found in Sand Paintings (or “dry paintings”). Sand paintings are a part of a very sacred religious ceremony for the Navajo people.

Did you know?

The Navajo word for Sand Painting is:

iikaah ("ee-EE-kah")

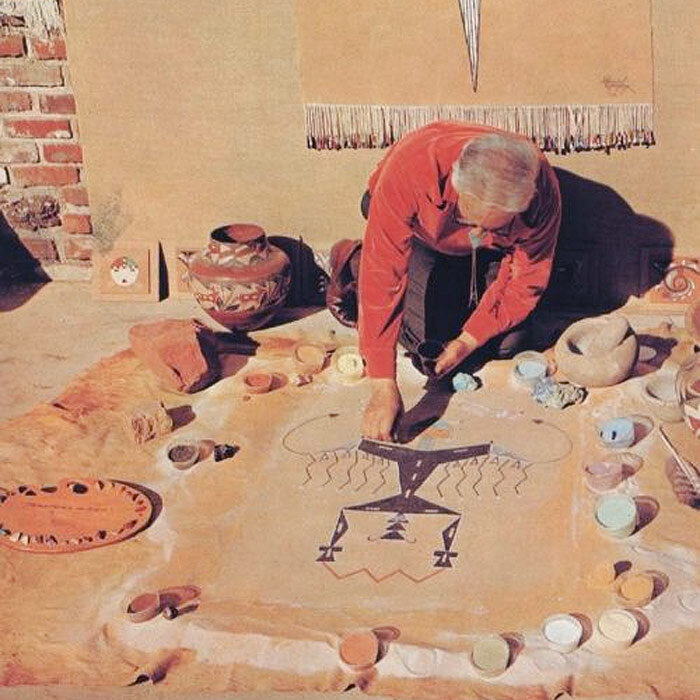

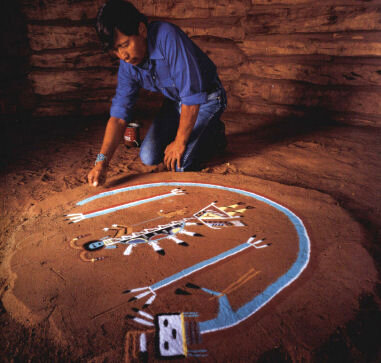

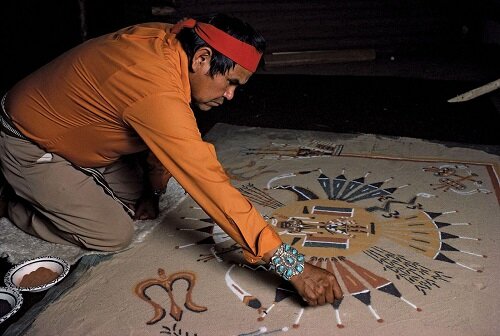

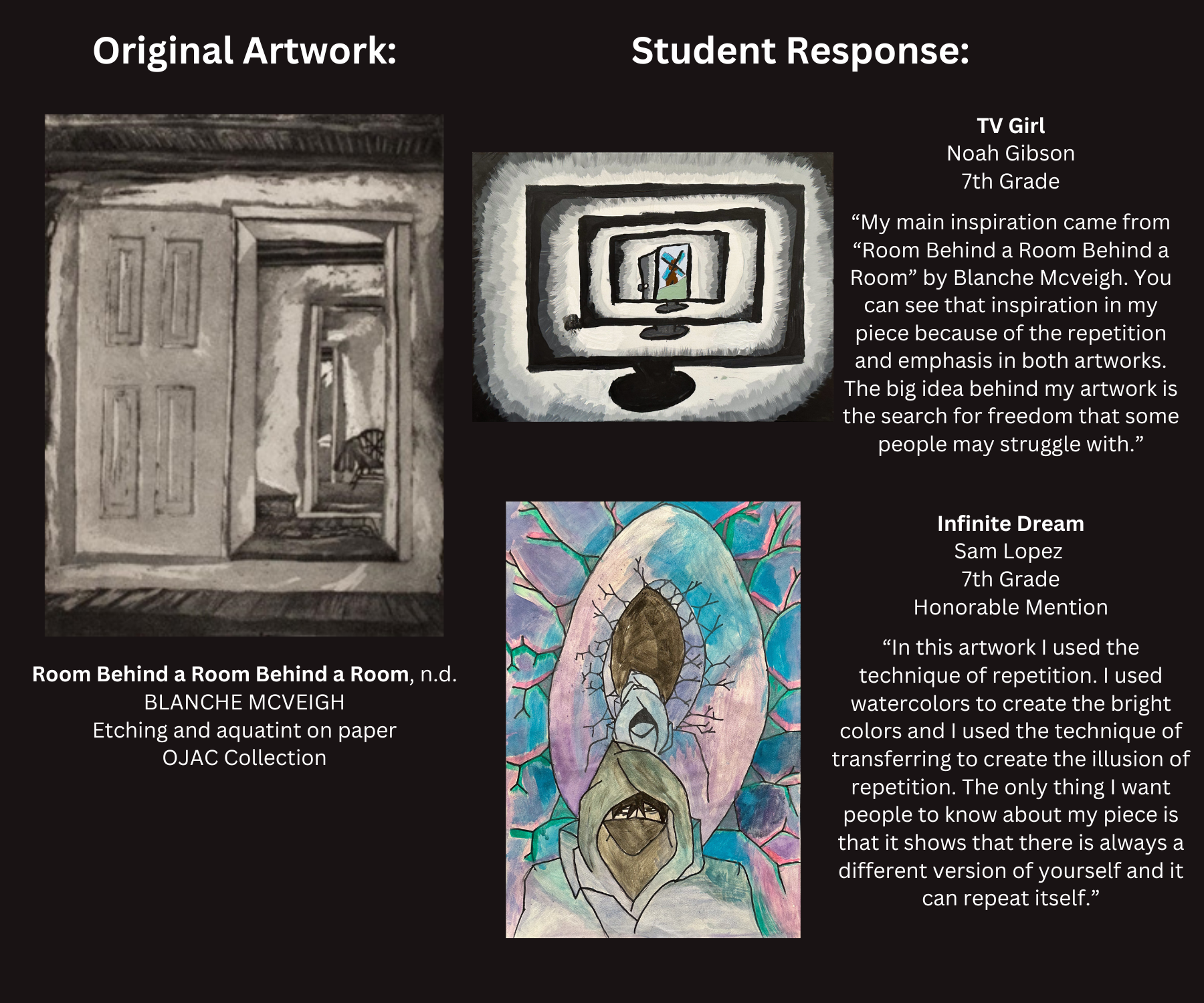

Observe the examples of Sand Paintings below.

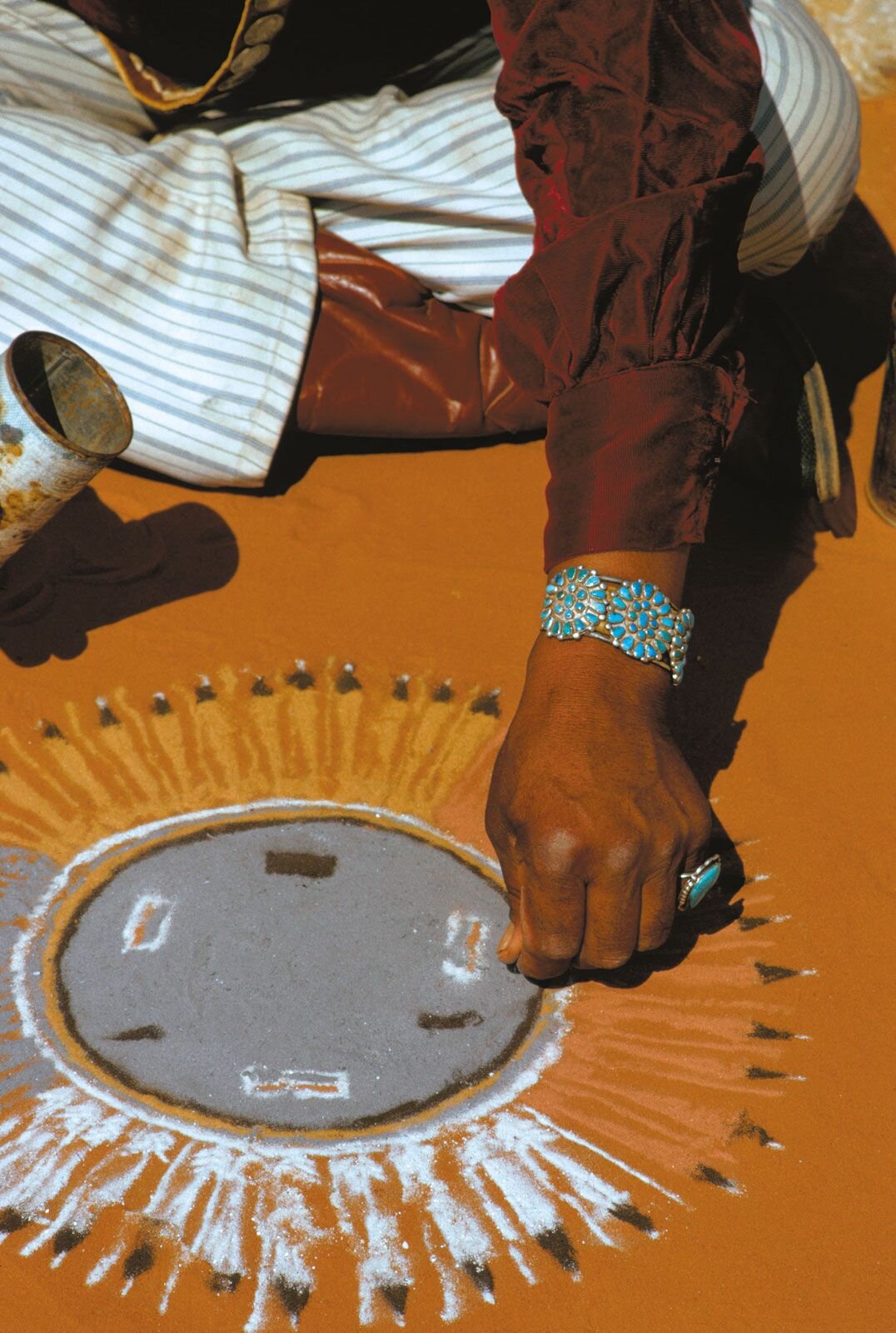

To create these sacred works, the Shaman of the tribe 'paints' by letting colored sand fall carefully through his fingers onto the ground, creating holy symbols and holy figures that are believe to heal.

After the sand painting is complete, a person who is suffering an illness or issue is asked to sit on the painting while the medicine man recites healing chants.

For the Navajo, the sand painting is a dynamic, living, sacred entity that enables a transformation in the mental and physical state of the ailing individual. They believe that the holy figures in the painting absorb the ailment and provide relief.

After the healing ceremony, the sand painting is considered toxic and destroyed because it has absorbed the illness or problem.

Traditionally, outsiders are rarely invited by the shaman to attend the sand painting ceremony due to it’s holy nature. The paintings are quickly destroyed after use as the image is believed to be sacred and and temporal (temporary). It is only meant to be seen by the ailing individual and the shaman- in fact, it is believed by many Navajo that the replication or publicization of these sacred artworks is a cursed activity.

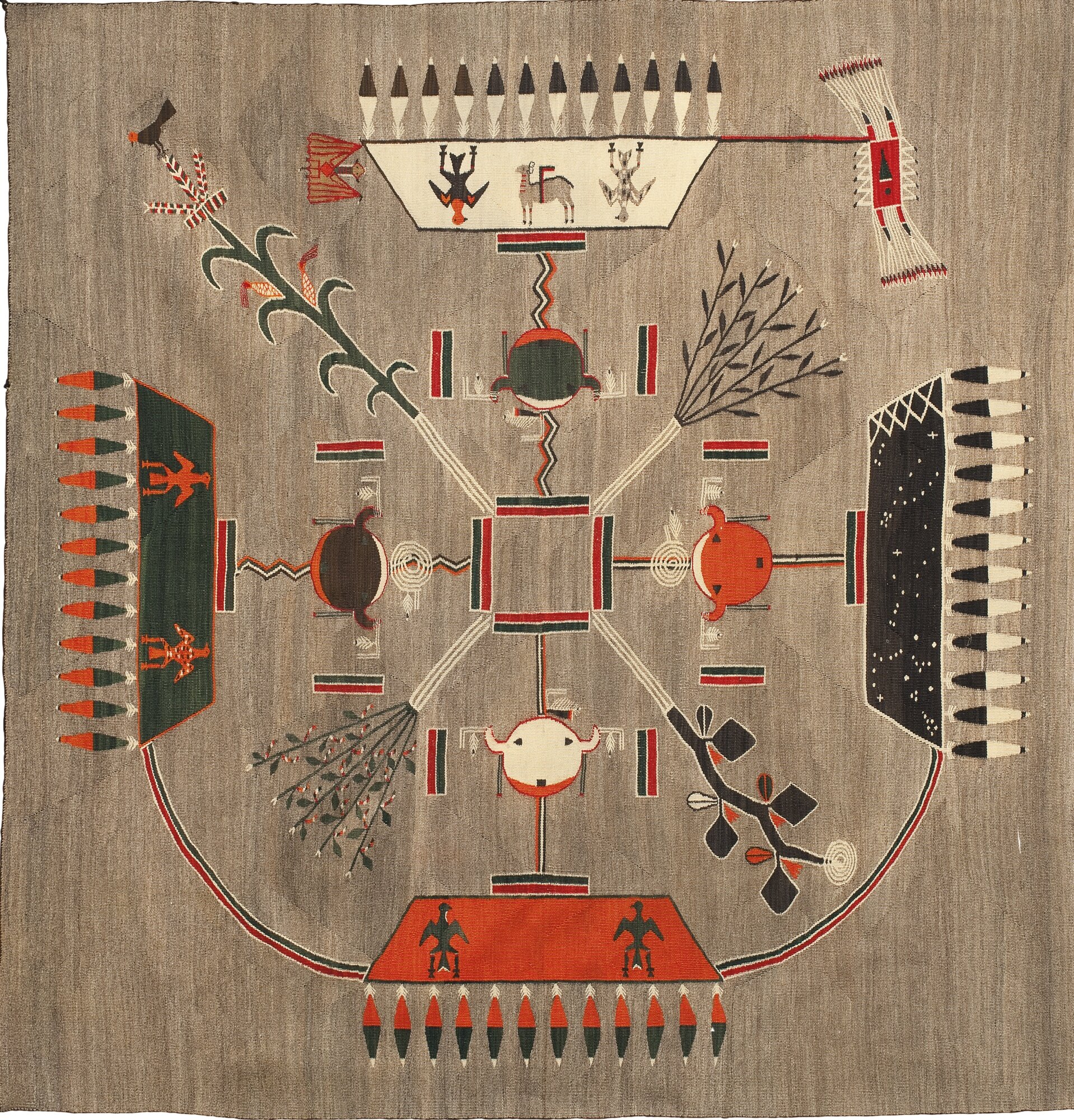

However, some modern Navajo now choose to permatize the sacred images (make the designs permanent) by turning them into weavings or prints that can be sold for a profit. The sand original is still destroyed. These Navajo Artisans usually make respectful changes to the original design (adding intentional errors and changing colors so it's not exactly the same).

Through these woven and printed replicas we can now observe the symbols and designs of these sacred ceremonies that were otherwise invisible to the public until the last century. We have examples of both in the collection of the Old Jail Art Center; I highly recommend you observe these unique and engaging works during your next visit!

Navajo Sand Painting Rug, c. 1930

NAVAJO

Wool

LX.036.01

Where the Two Came to Their Father, nd.

Navajo Ceremonial Sandpaintings

Book of Prints

SC.120

Erin Whitmore, Education Director