An acclaimed exhibition series, the Cell Series presents living artists and their work. It offers a rare opportunity to encounter work that is attempting to interpret and translate the world we universally experience in unique and surprising ways. The founders of the OJAC were passionate about supporting and showing living artists and their work - the museum continues this important mission with the Cell Series.

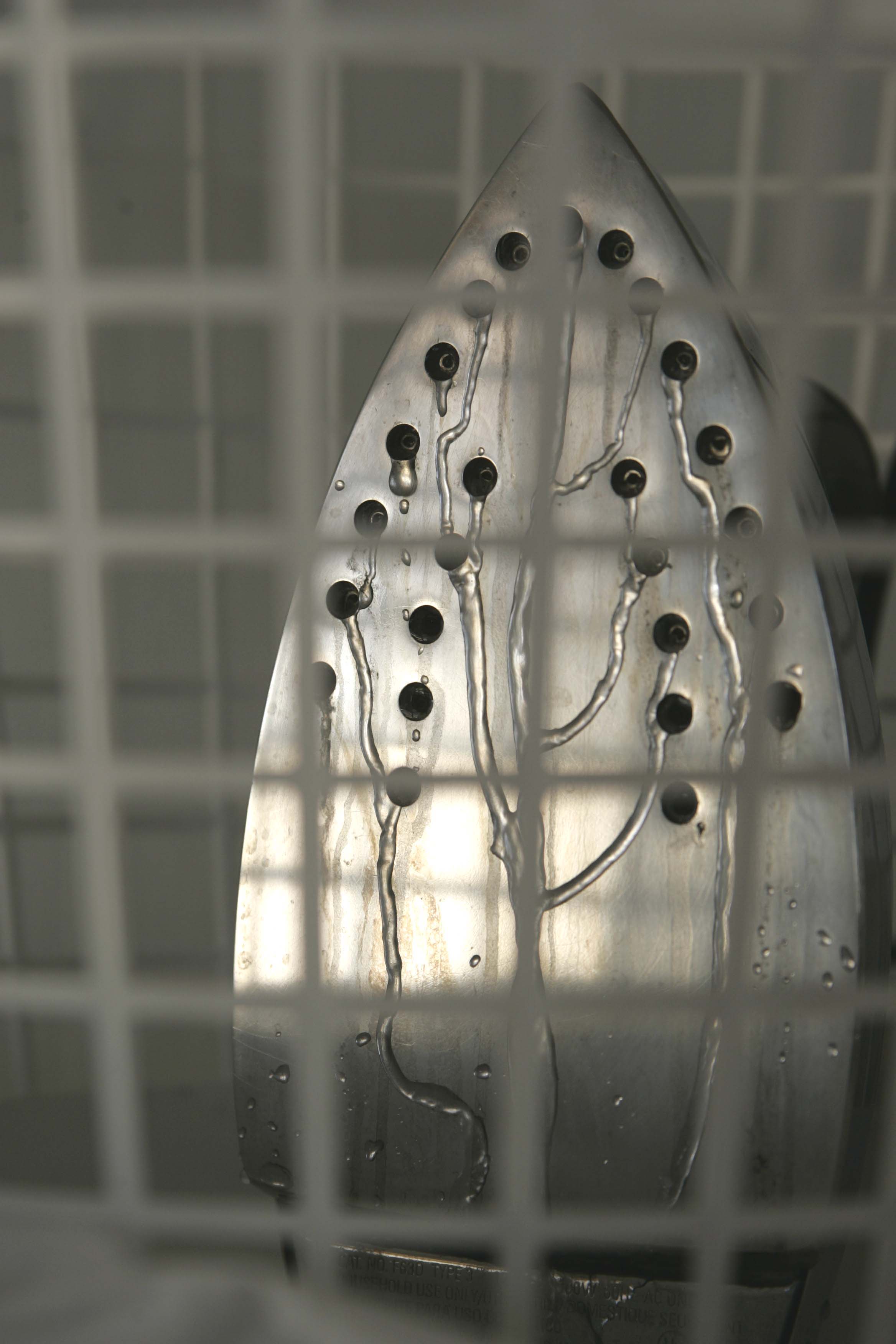

Helen Altman’s work centers around common materials, objects, and images of animals and nature. The objects she utilizes in her work often derive from the flawed or discarded. Altman then makes alterations to these objects elevating them into the realm of “art,” thereby forcing interpretation of her choices and manipulations. Handmade moving blankets embellished with animal imagery represent change and impermanence along with insulation and protection. Drawings of animals burned into paper using a small propane torch suggest the fragility of animals and nature. Domestic items like a continuous “weeping” iron among a large pile of men’s shirts references individuals trapped in pre-defined roles.

Her choices in material and imagery are broad; their humor and absurdity lead to deeper interpretations associated with loneliness and isolation among overcrowding, separation, and the loss of individuality and identity.

For the OJAC’s Cell Series exhibition, Altman includes never before seen works from her household “habitat” collection—common objects that started out as personal collection objects of the artist. The installation also incorporates her iconic “altered appliances,” woven wire birds, and a series of seed and spice skulls.

Helen Altman was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama and currently resides in Fort Worth, Texas. She earned her BFA in 1981 and her MA in 1986, both at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, followed by her MFA in 1989, from the University of North Texas, Denton. Her work is included in the permanent collections of the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the Sarah Moody Gallery of Art, the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa. She has participated in numerous museum exhibitions including solo exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego; the Glassell School of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the Grace Museum, Abilene. Selected group exhibitions include the McKinney Avenue Contemporary, Dallas; the Museum of Arts and Design, New York; the Old Jail Art Center, Albany; the Meadows Museum, Southern Methodist University, Dallas; and the Chelsea Art Museum, New York.

Helen Altman Interview (April - May 2018)

Patrick Kelly (OJAC Executive Director and Curator): Before we begin any conversations specific to your artwork, I would be interested to know about your background and if it influenced your work. Where you grew up, were you always interested in making things, those types of things?

Helen Altman: Ok great, this is a fairly easy one. I grew up in a regular urban neighborhood in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. As a little kid I remember being so excited when my older sister would go and dig clay out of a nearby cliff. That’s what we called it…”the cliff’.” She’d mix that clay to the right consistency with just enough water and we’d make things. Later on, a special treat was to get to go and buy a 25-pound block of clay from a place called Ham’s Pottery outside of town.

Visiting my grandmother’s house and barn were also special. Going to look for and collect the chickens’ eggs at the barn was always a magical event, although you couldn’t get out of the house without a warning about snakes. My mother made an effort to take us places like local lakes and arboretums. I think I inherited my love of nature from her. So yes, my early background definitely influenced my later work.

As an undergraduate, I had more classes in biology (fish, insects, and plants) than I did in art and art history.

PK: That explains the recurring imagery and subjects related to nature and animals in your works over the years. One of my first memories or encounters with your work was your use of fake fire logs en masse. Those were both humorous and disquieting at the same time. Can you recall where the idea of utilizing them derived?

HA: Yes. The first time I saw them was when I was around 9 years old at a neighbor’s home. At Christmastime this neighbor would set up a painted cardboard fireplace that used a set of these electric logs. And I remember being amazed by them then. My own home had a “real” fireplace and we enjoyed “real” fires every winter. But the sensation and effect of that fake set stayed with me. As a grad student I started collecting the electric logs when I would spot them at flea markets. I was unable to find enough of them second-hand to use in my work but did discover that they were sold new at fireplace accessory stores. I actually got “dealer” status from a company called Rustic Craft. And at one point I think I owned over 150 sets. I had the choice of about 20 different styles in both birch and oak. The company also accepted my designs for custom-made pieces like the “Corner Campfire” and “X Log.”

PK: So, was it a conscious endeavor to carry on the “fire” theme when you started creating your torch drawings or were those spurred by another inspirational factor? Can you describe how those drawings are created?

HA: The torch drawings came about because of a 1991 group show I was asked to participate in, titled Metamorphosis of a Butterfly. Everyone in the show was given a “butterfly” type chair to use, to change and reformulate it with no restrictions as to function or media. I decided to make my chair look like it was on fire by wiring it up with flicker flame bulbs. To enhance the effect of burning, I decided to burn the canvas of the chair with a propane torch. Immediately I saw that I could control the burning of the cotton canvas of the chair. The next day I practiced burning the shapes of leaves onto wet printmaking paper, which is also cotton. So that piece of sculpture led me to the torch drawings. The very first drawings were done on my oven door. The insulated door distributed the heat pretty well and wet paper doesn’t ignite immediately. I now use a four-foot square sheet of stainless steel to stick the wet paper onto. The Reeves type cotton printmaking paper has stayed the same. It needs to be soaked at least a day before burning. If I work too long on a drawing, it dries out and catches fire. And the drawings don’t lend themselves to being re-worked. I work from projections and when I get a good result, it is soaked again and then dried under weights in between cloth blotters for a couple of weeks.

PK: At this point did you think about the two series (fire logs & torch drawings) and recognize the “fire” theme and try to analyze what, if any, meaning it had to you? Or perhaps it was just happenstance?

HA: I don’t think I ever analyzed it more than thinking that I liked things that do things simultaneously, although they seem to contradict each other. The fire logs were both convincing and blatantly artificial at the same time, and the torch drawings could be both exact and profoundly blunted and abstract. I loved the fact that the tool (the propane torch) took all traces of my hand out of the drawings. The fire logs were fabricated by someone else, and came back from the factory stranger—and I think better—than I ever could have made them.

PK: I think those dualities are abundant in your work—contradictory as well as synonymous. Did your “altered appliances” begin prior, during, or after your fire logs? Can you describe idea(s) related to those?

HA: The altered appliances started prior to the fire logs, around 1988. I found I could make commonplace objects more interesting by altering them in ways that included a history of something else. Blenders contained spinning tornados, mixers had tiny chrome jets instead of beaters, water fountains had cast water whirlpools with little ships going down the drain, and a weeping iron sat trapped inside a laundry basket. I liked making things move and lighting them up. Is anything so comforting as the light inside a refrigerator? I remember liking that the objects took on lives of their own when I finished with them—like the owner disappeared but they kept going.

PK: Your cast human skulls using natural materials may be one of my favorite series. How did the cast skulls come about? What challenges did they present?

HA: I had seen cast birdseed bells in stores that are made for birds, and I found the shape of the bell an odd choice for a feeder. I was familiar with the Day of the Dead sugar skulls and liked the imagery. So, as a lark more than anything else—and what a great pun that is—I made a mold off a medical skull replica I had, then fiddled around with what to stick the seeds together with. I wanted them to be all natural and edible for wildlife. With a good bit of experimentation, I wound up using a mixture of concentrated gelatin and sugar to coat the seeds. The mold was packed with the sticky seed mixture and then frozen solid. I could remove the cast seed skulls from the molds when they were frozen. They were then dried in front of a fan for a couple of weeks. I hung the feeders on my clothesline and watched the birds during the day, and the rats in the night, eat the skulls. At a local feed store, I was able to purchase all sorts of different colored seed, not just birdseed but also grasses and other grains. The skulls looked so pretty on the clothesline that I decided to make a larger grid of them to be hung on a wall. I’ve used all sorts of seed and then started using spices, teas and all sorts of fragrant ingredients to make the skulls. I know I have made hundreds of them. Some of my favorites were made with balsam fir, which I hung in my bathroom. After every shower, the room smelled like a Christmas tree. So for me, the skulls are much more about life and the rich and wonderful smells of spices for cooking. There were challenges. Unfortunately some of the media I used had the tendency to attract small beetles and pantry moths. One large installation had to be fumigated mid-show.

PK: I’ll refrain from asking about every body of work since you have many various ones—often creating them simultaneously. But one constant is depicting animals in both your two and three-dimensional works. I likely know the answer, but can you explain why animals reoccur?

HA: Animals and nature are a constant source of pleasure for me, both in my work and my everyday life. Something that I am delighted by each summer is when American toads come to mate and leave their eggs in the pools I keep set up specifically for them in my back yard. I get to hear the calling males and then see the beautiful strings of eggs left in the ponds the next morning. In as little as two days the eggs hatch, and in as little as two weeks the hundreds of tadpoles morph out of the pools as little toadlets. Also this spring, even before the toads have started to call, a pair of Wrens nested inside my kitchen, and raised their babies! These are my great moments.

PK: Along with the title “jailbird,” can you discuss your installation in the OJAC cells?

HA: The title has so much to do with the space of course and also other things. The installation will include works that span over 26 years. I’m going to be showing works and collections that I live with on a daily basis. Some of these have not been shown before. I hope to create a displaced personal habitat. (Maybe like someone jailed would do with collections of personal artifacts on the walls above their bunks.) And just so you know, to this day I still don’t understand my attraction to toy brooms or child sized feather pillows. Some of the works being shown have obvious references to being trapped or jailed, like The Weeping Iron, and the collection of chocolate molds that to me look like trapped animals. I’m calling those captives.

PK: OK….now for some personal insights. You and I have known each other for a long time now. One thing I have admired (and am admittedly jealous) about you is your ability to support yourself on your art. This is very rare, but I know it has been tough as well. Can you tell me about this “glamorous” life of an artist and what maintains you?

AH: You know I worked part time as a studio assistant for Vernon [Fisher] for 20 years. I started in 1988, while still in graduate school, and quit in 2008. So I’ve really only been supporting myself totally on my art for the past 10 years. I consider myself very, very lucky in that respect. I work from my home, which is mostly my studio. There is no china cabinet or dishwasher, but I was able to buy the house in 1999 (after 9 years of renting) before property prices skyrocketed here in this area. I have lived like a student most of my life. Almost every piece of furniture I own was dragged in off the street or given to me. I had my first professional haircut in over 30 years for the opening in Tyler last month. (It was so expensive; I’ll never get another!) Up until last year, I drove a 1993 Honda Civic. When it blew a head gasket, I had to break down and buy a “new” used car, a 2007 Honda CR-V that is really nice. The air conditioner actually works in that one! I don’t have any family. I never understood how people could afford to have kids. I have dogs and chickens, and it seems at times I spend half my money on dog food, birdseed and meal worms. I worry about money all the time. I worry that sales will slip, and what sort of job I might have to find. I worry that I’ll run out of ideas that are exciting enough to act on. Lately, I’ve gotten so much more compulsive about buying things for my work; I purchased over 14 paper cup dispensers because I wanted to alter them. I’ve completed two but there are 12 left hanging on the wall, waiting on me.

As for what maintains me…times like today, I really wonder. I try to find joy in small stuff...like there is nothing better than lying down on clean, line-dried sheets, and having a good book to read at night. I love hearing the different creatures I care for here go about their lives. I made a staircase out of three kid’s toy pianos for my chickens to use to get to and from their nests where they lay their eggs. So several times a day I get to hear the chickens playing the pianos. Stupid stuff like that just cracks me up. I don’t laugh nearly enough. And I told you about the wrens making their nest in the kitchen. That brought me a lot of joy.

PK: Hypothetically, lets say another type of success happens where you’re selling works and making a very “good living” on the sales. With that idea in mind, would you anticipate that type of success changing your work? What type of work would you do? Would you be compelled to keep doing what is successful vs. what you think is meaningful?

HA: Another type of success would involve having a back rub once in a while and maybe something done to the bags under my eyes, the hump on my back and my nutrition in general. I’m cracking myself up with these answers.

I don’t think I’d ever make another wire bird or any sort of painting. I’d make work that stems from boredom. Time is truly a gift; time enough to get bored is a priceless luxury. When I get bored I make funny stuff. I constructed a living banana boat of free ranging fruit flies in my kitchen window so I could watch their life cycles. In time they took over the whole house. (And drove my former partner nuts! It was one of the greatest passive-aggressive ideas I’ve ever come up with.) Giving yourself the time to wait for the perfect answer is such a rare thing. I’d probably make a lot more record players, and altered appliances that leak and spew and shine from within…but are impossible to sell and maintain. I’d have a talented technician to keep them running, so I don’t get frantic calls in the night saying things have gone dark, or melted, or spilled pigmented fluid all over a custom built counter and the museum floor.

I’d become a writer, and write about all this.

The 2018 Cell Series is sponsored in part by Susie & Joe Clack, Amy & Patrick Kelly, Gene & Marsha Gray, Sally & Robert Porter and generously supported by the McGinnis Family Fund of Communities Foundation of Texas.