Houston artist Francesca Fuchs seeks to understand an ordinary object or another painting by…painting it. Her depictions are not verbatim, but appear as ghostly doppelgängers created in thin veils of pigment on canvas. Most often, the painted object is one that Fuchs has a personal connection to or that is from her childhood home. She may choose to paint a framed photo of a 1960s dental office, a lady bug rock she created as a child, a framed Piranesi print, or a sculpture of a reclining figure.

For Fuchs’ exhibition Francesca Fuchs at The Suburban at the OJAC, she painted “objects and paintings she did not know in person for the first time,” and instead focused on works in the OJAC’s permanent collection. Perusing some 2,300 digital images on the museum’s online database, Fuchs sought other artists’ works that inspired her. Surprisingly, her intuitive choices were, more often than not, works that often garner less attention than the more “significant” works by any particular artist. Destined to be the subjects of her re-making, her selections are indicative of her attention to things we often dismiss or deem insignificant in aesthetic hierarchal systems.

The enigmatic title is a reference to a past exhibition of her work at The Suburban in Illinois in 2013. Fuchs “re-creates” and references that particular exhibition creating conversations between a suburban space near Chicago and a rural space in west Texas. Simultaneously, relationships echo throughout the entire exhibition as a larger conversation occurs between her paintings of paintings and paintings of objects within the OJAC galleries.

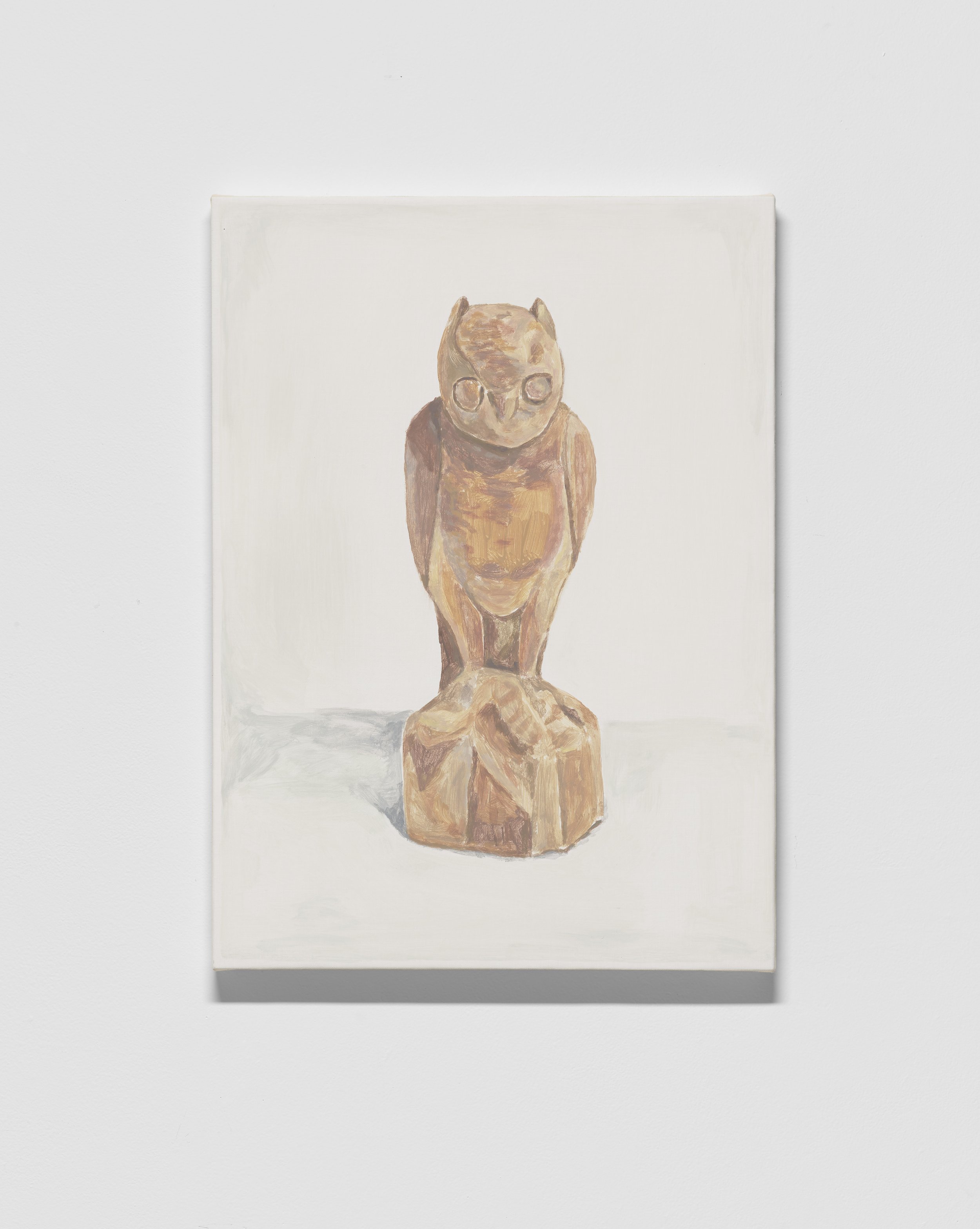

FRANCESCA FUCHS, Owl from the OJAC, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 22 x 16 in. Courtesy of the artist, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX and Inman Gallery, Houston, TX.

Installation images courtesy Kevin Todora.

Patrick Kelly, Old Jail Art Center Director and Curator, interview with artist Francesca Fuchs

PK: Your work that I am most familiar with usually includes a depiction of an isolated object that you render in washes of pigment. The results are ghostlike images that feel intimate, fragile, and susceptible to disappearing… much like a memory. When did you first begin this painting approach or “style”?

FF: I want to focus with tenderness on one thing. The painted object is often one that comes from my personal life. I am interested in how the personal object translates into larger mythologies and histories, how there is an archetypal sameness, yet an absolute uniqueness to each thing: its thinginess. I try to translate that essence with touch and color imbuing the painting with a true sense of the thing and my love for it. I would like for the painting to hold as much or more magic than the object itself and for the painting to sit on the cusp where it is fully present and something that is continually coming into being.

PK: That’s tricky territory as it seems difficult to portray sentiment without being sentimental in the arts. Yet, as a viewer, I don’t feel you are taking that easy path of using blatant sentimentality to engage a viewer. Your work is successful perhaps because the objects are exclusively personal. Do you feel that painting an object or another painting is a means of understanding that object that can’t be accomplished by any other means?

FF: I sometimes paint the same object or painting more than once. I also write about the objects. As part of the exhibition Serious and Slightly Funny Things, we made a book in which I include a short description of each painting in the exhibition. Writing feels vulnerable and revealing in a different way. These written descriptions verbally revisit the balancing act that the paintings are trying to hold: keeping the information bluntly straightforward, but then slipping into an intimate or personal thought. The slippage is something I am very interested in. The place where things shift and change and open up. There is an edge that I sometimes feel could be lost with one brushstroke. I try to get the paintings to that point where they are just there and no more, and that is everything and almost nothing. I think sentimentality doesn't have much room in that space.

PK: Do you recognize, or have, criteria for selecting a subject to paint?

FF: I need to feel a connection to the subject. It needs to remind me of something, embody an archetypal role of a type of painting I know deeply—a type of landscape painting, a still life, a type of abstraction. I believe art making is a collective endeavor. We build on the things we know and have seen. To me things we live with in our private spaces are as important as the things we see in our public spaces. I believe all forms of making to be truly equal—in antiquity or now, whether made by child, adult, trained, self-taught, known, or unrecognized artist. We build on each other in all ways through time and space. Something original is an evolution out of other things that reaches a momentarily delightful and surprising outcome. Artmaking is confluence.

For this exhibition at the Old Jail Art Center, I am painting objects and paintings that I do not know in person for the first time ever. I selected them very intuitively by combing through the online archives of the Old Jail's collection. My focus was on modernist abstractions, women, vessels, nature, but also a sense of power and place. I am interested in how we signal the importance of objects both personally and collectively, and am drawn to the fissures between what is seen as 'important' or 'unimportant.' After all, many museum collections were started by women's art leagues.

PK: The art world seems to run counter to some of these beliefs or perhaps it spurred your interest; specifically, the hierarchy of creators and the value that is attributed to some objects and not others. I did note on a studio visit, it was interesting that you selected some works from our collection that we deem not as “important” as others and that don’t get the attention they should. I’d advocate museums (art, natural science, history) periodically allow artists to curate exhibits from their collections…would you agree?

FF: Ascribed artworld values are confusing and at times absurdist. They exist on a measure scale that is to the side of our looking, making, and thinking about art. Focusing on pieces in the OJAC's collection that are not deemed "important" (your word) was certainly in my thoughts. I do however make a painting of a Henry Moore lithograph. Not because it is Henry Moore, but because I wanted this reclining female figure to be part of the grouping.

Some of the more exciting exhibitions I have experienced are ones where artists curate from museum collections or where curators bring objects from very different times and places together into surprising new conversations. The Menil Collection has been a seminal influence here. There was Robert Gober's The Meat Wagon in 2005 and so many other specific exhibitions I can think of. I am planning to include at least one actual object from the OJAC's collections into this installation, possibly more.

PK: Once these works are installed in the context of a gallery space, can you talk about the anticipated dialog or relationship between the paintings?

FF: Thank you for asking this question, Pat! For me, the relationship and conversation between paintings in an exhibition is as important as how each individual painting works. I spend a lot of time in the studio working with models and I mock up relationships on my studio walls. I want to create conversations between pieces that resonate deeply and intuitively. For this exhibition, I want paintings of paintings that I grew up with to interact with paintings of paintings from the OJAC's collection. In the OJAC's Jones Pavilion I am hoping to create a giant conversation about painting by placing all works fairly close together, creating references and echoes between pieces—whether the original was made by my aunt Charlotte Kell, by Henry Moore, by me, or by Jewel Nail Bomar. I am also very interested in placing paintings of paintings next to paintings of objects. They clash a little and unsettle each other—one sets up a traditional picture plane, the other denies it. I also want patterns and colors to resonate across time and place—like an Acoma Pueblo pot and a 70s brown braid supergraphic.

PK: That relationship and conversation is very important to me as well, for more reasons than we can get into in this interview. Well, let’s talk about the title you composed for the exhibit—Francesca Fuchs at The Suburban at the OJAC.

FF: I made a show with Michelle Grabner and Brad Killam at The Suburban, in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago in 2013. For me it was an important show at the time, taking my work outside of Texas. The OJAC's Nail Gallery struck me from the beginning as a 'treasure' room—a space that was in some way at the heart of how I was thinking about this exhibition. I re-make things to hold them up, to think about them and to recontextualize them. I re-paint paintings, I re-make mugs and re-paint objects. As part of this solo museum exhibition, I wanted to re-make an exhibition; borrowing paintings back, to bring this moment from a different time and location—a little gallery outside a suburban house, a decade ago—into the heart of the Old Jail Art Center in Albany, Texas. There is something funny and strange about that. As part of this OJAC revision, I am also looking at some of the artists of the Fort Worth Circle in the OJAC's collection such as Flora Blanc Reeder, and even peripheral artists like Jewel Nail Bomar. Maybe I am asking the question of what it is to be seen as a Texas regional artist, and in particular a female regional artist. The title reflects that. It is a box within a box.

Francesca Fuchs at The Suburban at the OJAC is generously supported by Sunday & Don Tidwell with additional funding from Paula & Parker Jameson and an anonymous donor.