Dallas artist Keer Tanchak’s initial desire to reject painting on canvas was further inspired by Mexican painter Frida Kahlo’s practice of reworking traditional Ex-Voto and Retablo paintings on tin. Tanchak often paints on irregularly cut aluminum sheeting that stands in stark contrast to her expressive, yet delicately rendered, portraits and vignettes. Her subjects are mined from art history books, magazines, and movie stills. Appropriated and recontextualized, the images often depict women and interiors throughout history that reflect on pleasure and wealth, the redirection of the male gaze, and traditional portraiture. The shaped paintings are experienced differently within changing environments and context. The OJAC’s jail cells are a prime and provocative venue for the interaction.

Patrick Kelly, OJAC Director and Curator, interview with artist Keer Tanchak

PK: It might be somewhat cliché, but I often start an interview by asking artists to talk about where they grew up and, if they choose, about their childhood. (You are welcome to recline on a couch to contemplate the answer.) The replies are often telling.

KT: A poem about childhood

born: North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

first few baby months: Bowen Island, B.C.

toddler years with grandma: Burnaby, B.C.

toddler years with mom studying MFA creative writing: UBC student housing, B.C.

kindergarten: Kimberley, B.C.

grade 1: Quilchena Elementary School, Vancouver, B.C.

grade 2: ?

half of grade 3: école F.A.C.E., Montreal, QC

half of grade 3 through half of grade 5: Roosevelt Elementary, Prince Rupert, B.C.

half of grade 5: Fairview Elementary, Nanaimo, B.C. while living on Protection Island, B.C.

grade 6 and half of grade 7: General Gordon Elementary in Kitsilano B.C. while living in East Vancouver, B.C.

half of grade 7, grade 8, and half of grade 9: Bella Coola and Hagensborg, B.C.

half of grade 9: UHill Secondary, while living in Marpole, B.C.

grade 10: Ratsgymnasium, Münster, Germany

grade 11 and 12: UHill Secondary, while living on University Endowment Lands, B.C.

PK: Well, that is very telling…perhaps at some point in the interview we will learn more about the reasons for the frequent moves. I will ask though, was there a constant in your young life that shaped or influenced your art practice (e.g., art, music, movies, etc.)?

KT: We usually had no television so I spent a lot of time drawing and going to the cinema. I was taken to museums when we lived in cities that had them. The neoclassical structure that houses the Vancouver Art Gallery is next to the Hotel Vancouver with its iconic green copper chateau roof. These buildings were noticeably different from the modern skyscrapers, boxy apartments, and rugged natural landscape that enclosed the city. I could only relate to them through children’s books. In fairy tales, castles or buildings with ornate columns were cues for fantasy and escape in connection to social class. I imagined the art museum did the same for the people and the artwork it contained. I’m told I had to be dragged out of the Picasso exhibit at the age of four because I refused to stop looking. As a teenager, the works I connected to most were by Emily Carr.

PK: I was unfamiliar with the work of Emily Carr. I looked up her work and really liked it. She handles pigment similar to Charles Burchfield whose paintings I also enjoy. As far as cinema, we have had conversations about movies, but I do not recall if there is a particular genre that you gravitate toward. Do film and movies inform your work?

KT: Yes! Carr and Burchfield’s styles definitely overlapped and we know from her history of travel that she was aware of his work. In other ways, Emily Carr is a little bit like Georgia O'Keefe. She’s known for painting outside in extreme conditions, and was written about as a lone female working at the periphery of men; in Carr’s case: the Group of Seven. She studied in France and brought a post-impressionist language back to interpret the west coast (of Canada). Her paintings were translations of our environment, fitting the perspective of the European designed museum they sat in. I liked them because they lit up and organized what was often very overcast and chaotic outside. In response to your question about film, there is no particular genre I favor. I think the experience of watching movies in repertory cinemas as a young person helped democratize the genre field and collapse a sense of time for me. I was equally excited about watching Hollywood produced Point Break as I was seeing a foreign produced period film like Orlando in the mid 1990s.

I remember feeling that paintings were like frozen moments of silence in film. A painting could harness all the emotional power of cinema without the burden of time and language.

Increasingly, I use film as a starting point in my work. My last show at 12.26 (Dallas) included paintings of actors in scenes I had photographed.

PK: When I first became familiar with your work you were painting on irregularly shaped pieces of aluminum sheeting which are reminiscent of retablos. Yet, the imagery derived from various pop, fashion, and art history. Can you speak to why you elected to reference and utilize that imagery on metal sheeting?

KT: There was a moment in my early studies when I was frustrated with traditional supports and looked for possibilities beyond canvas, board, and paper. I wanted a smooth surface I could hand cut that wouldn’t flop over when quickly propped against a wall. Luckily, I was taking an art history class on Frida Kahlo and learned about the genre of devotional paintings on tin she had been influenced by. I also admired Gary Hume’s painted hospital doors, Jennifer Bartlett’s post-minimal grid plates, and Frank Stella’s shaped reliefs—all made with aluminum or steel. I've been thinking about the relationship between the intimate retablo and the industrial futuristic qualities of metal ever since. I really wanted to occupy both worlds.

But I don't see my choice of subject and medium as simultaneous decisions that couldn't exist without each other. I also paint on paper and canvas and I even work with aluminum in ways that disguise its inherent qualities. To me, a mark on paper is as important as a mark on canvas or aluminum. I can’t stand the idea of a ‘preliminary sketch’ on paper that gets shoved in a drawer or the guiding outline that gets buried under layers of more worthy paint. Urgency has always been my main interest and this also applies to the subject matter I choose.

PK: I completely understand the metal being a desirable surface to manipulate pigment. If you recall at our studio visit, we talked about “objecthood” by working on the shaped material…the idea that the work becomes a hybrid—a painting to be read as such and/or an object. Do you consider that, or is that just my hang-up?

KT: Ha, ‘hang-up’. (Cute in relation to convo about painting.)

My studies also had me questioning image/object, as if the two were eternally positioned against each other. I felt dissatisfied with what seemed like pressure to choose and ambivalent about not taking a stance.

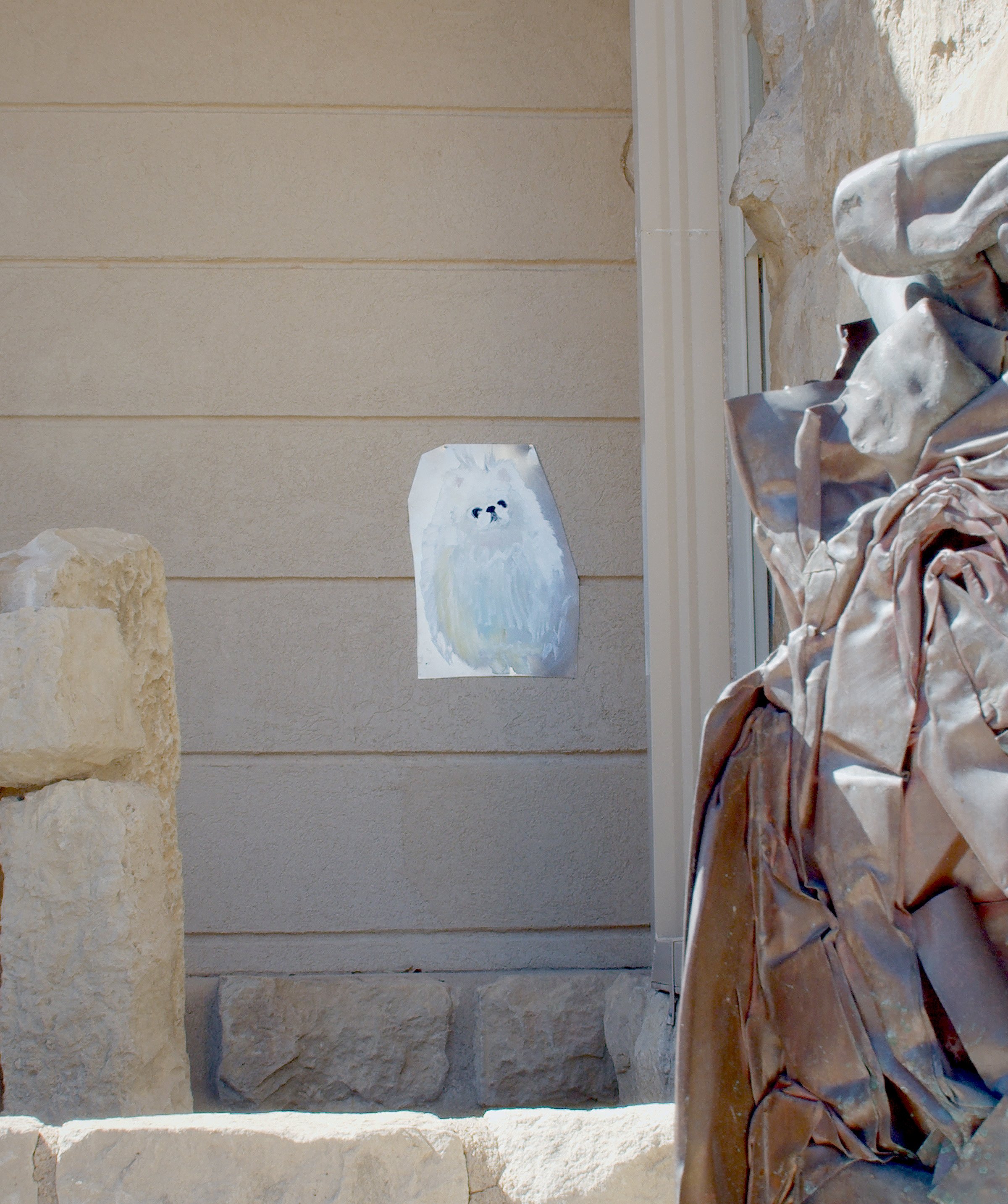

I think I’m more interested in seeing if they can hold hands without disappearing into each other. I’ve looked to artists that work with images and objects in a way that can feel playful. Karen Kilimnik’s paintings and ‘scatter art’ installations can be confounding and awkward but lure you in with intimacy. And, of course Alex Katz is the champion of painted pictures and painted shapes. His canvas paintings and shaped aluminum cutouts simultaneously occupy spaces without any sense of hierarchy. He frees his characters from their backgrounds allowing their silhouettes to interact with changing environments and contexts of museums and galleries. I really relate to his instinct.

Often, I see my painted cutouts as mysterious clues in my studio, waiting to be puzzled into the idea of a picture and/or organized into the experience of an exhibition. But my first shaped pieces were born from the opposite instinct. I was circling and saving what I thought were the best parts from failed compositions.

PK: That leads perfectly into talking about your exhibit titled Company Retreat in the OJAC’s Cell Series. Would you talk about your intent with this exhibit…knowing that during the installation process things may change due to unplanned “interactions”?

KT: The cells at the Old Jail Art Center have beautiful natural light and herringbone patterned brick floors. My first impression was that it was nicer than most apartments I’ve lived in. It’s not what one expects to find in a space with a history of incarceration.

There is a sense of theatricality when ascending the staircase between the two rooms of the jail. It’s hard not to imagine the power of the reveal for a viewer entering the space, so I wanted to evoke something visceral. I often work with exaggerated scale, repetition, and sentimental subject matter to do this.

What does it mean to show art in a former jail cell? It seems impossible to ignore the context. The results have come from thinking about attraction, repulsion and evasion. My first thought was: ‘Who do I want to see in jail? This evolved into: ‘What will make this space feel lighter emotionally?’

I rarely feel a sense of resolution in the studio after putting down the brush or metal snips; to me the work is only complete when it takes its particular stage. It’s because of this that I’m grateful to be asked to make work for the cell and museum. I’m really interested in the way architecture and its history and contents influence us. Responding to a specific place adds a layer of empathy and meaning to the work that is unique.

During my site visit, a fleeting glance at cutout toy ballerinas in the Robert E. Nail Jr. Archives led to a lingering feeling to answer back. They hinted at what was once important to a child in the region. It’s in this spirit that I’m less interested in locking characters into a picture than I am inventing them with paint, assessing their boundaries, and freeing them from narrative.

The 2023 Cell Series of Exhibitions is generously supported by McGinnis Family Fund of Communities Foundation of Texas, National Endowment for the Arts, and Kathy Webster in memory of Charles H. Webster, with additional funding from Lucy & Fowler Carter, Margaret & Jim Dudley, Jenny & Rob Dupree, and Dr. Larry Wolz.