OJAC Cell Series of Exhibitions

Colette Copeland’s fascination with Jesse James stems from childhood family lore and tales of her blood kinship to the notorious outlaw Jesse James which manifested into an art project. Copeland’s ongoing project, My Jesse James Adventure, goes beyond the personal connections through heritage. It examines fake news, gun violence, criminal celebrity, the fascination with DNA networks, and fact vs. fiction. Over the years, the project has taken the artist to sites across the US where Jesse James lived and outlawed, filming and leaving her DNA in the form of a lock of hair at each site. The performative journey/quest thus far has spanned nine states and over 4,000 miles. Each new discovered site provides another topic or concept that the artists mines and layers into each new installation.

The OJAC’s Cell Series iteration of her project includes a 22-channel video installation; photographs of DNA hair offerings at each site; as well as a spaghetti western inspired musical score composed by Dallin B. Peacock.. The immersive installation prompts conversations about our “cultural” heritage, posing questions rather than seeking to resolve them.

Image: COLETTE COPELAND, My Jesse James Adventure (gunscope), 2020. Photo by Diane Durant.

Patrick Kelly, OJAC Director and Curator, email interview with artist Colette Copeland (April 2022)

PK: Before we discuss your exhibition My Jesse James Adventure, I’d like to ask about you. In these interviews, I sometimes begin by asking artists to reveal some background information—where you grew up, went to school, or currently reside. Importantly, feel free to expand on any events that may have impacted your art work. The question seems innocuous but it can be revealing and interesting to readers.

CC: Before my mother died, she presented me with a childhood psych evaluation from 1972. I sometimes use this as an artist statement of sorts. (illustrated) The psychiatrist was concerned about my excessive fantasizing and imaginary friends and wanted to medicate me. Thankfully, my mother disagreed with his assessment. He dismissed the importance of creativity and imagination as a vital component for childhood development. Reading this as an adult, I realized that the thematic basis for much of my artistic practice was already rooted by age six.

I played by myself a lot as a child. My father disappeared when I was eight and I wasn't allowed to play outside due to circumstances surrounding his disappearance. I spent hours creating my own worlds. I give a lot of credit not only to my mother's encouragement of my creative tendencies, but also my 2nd grade teacher, Mrs. Mandic. I made a blue fur hand puppet named Psychedelic, who came to school with me every day for the entire year. Mrs. Mandic allowed him to participate in all classroom activities including a cupcake birthday party for him. By today's standards, that behavior would be labeled at best as disruptive.

My life experiences as well as my surroundings shape much of my artistic work. I get my best ideas while I am dancing. I take dance classes 3-4x a week not only for physical and mental health, but to generate creativity.

PK: That’s insightful! I think many creative individuals can tell similar stories. The lucky ones have people who nurture those tendencies that fall outside the “norm.” This answer could take us down all sorts of rabbit holes but I’ll try to stay focused. Can you talk briefly about past works or projects that lead up to the current project?

CC: I grew up hearing stories about our family connection to the notorious outlaw Jesse James. When I moved to Texas 11 years ago, I knew I wanted to do a project about the subject, but didn't have a clear idea about the direction or approach. The project that informed my methodology was Becoming Colette. I was named for the French author Colette. As a young adult, I pored over her books and later her autobiography looking for similar characteristics to my namesake. In the summer of 2015, I traveled to France, filming at the sites where Colette lived and wrote. The resulting exhibition featured video book sculptures and a series of prints that simultaneously revealed and obscured aspects of the woman and the writer, as well as her connection to place. I coined the term "performative journey" to describe my process as an artist, researching the past, walking in the footsteps of my namesake, as well as looking for clues in the present-day sites. An amateur visual anthropologist of sorts who takes a lot of creative liberties. My Jesse James Adventure was a natural progression from that work. Researching Jesse James (both fact and fiction) led me to another performative journey—this one spanning three years, nine states and over 4,000 miles. Thankfully my journey was in a car and not on horseback.

PK: Your process is immersive; some might say to the point of obsessive. I don’t say this in a negative way because most artists do have obsessive tendencies…that’s why not everyone is a dedicated artist, or a doctor, or scientist, etc. So, what indicator must be present to say, “this project is now finished”?

CC: I am laughing about the phrase obsessive immersion, since that accurately describes me. In the case of My Jesse James Adventure, I am not sure it is finished. I thought it was complete two years ago after the debut installation at SPIN Gallery in Dallas. But the opportunity to exhibit at the OJAC and Jody Klotz Fine Arts in Abilene have allowed me to create new works for the project. I spent the past year producing solar plate etchings from my photographs taken during my performative journey. For the OJAC exhibit, I’ve created a new installation using photographs taken from my DNA hair offerings at each of the sites, which haven't been shown before. This year, I discovered a connection to Jesse James in McKinney, Texas, so there may be another exhibition there. With other projects, it's easier to determine the end point. Currently, I am working on three performance video projects. Once they are shot, edited and my composer completes the scores, they are finished. The next step is marketing them to festivals and museums/galleries.

PK: Are the performance/videos part of the Jesse James project?

CC: No. These are three separate projects. The filmmaker who I've collaborated with for a number of years has been busy making feature films, so I haven't made a video in which I performed since 2019. One project tentatively titled, Galaxias tou Gala (Milk Galaxy) features me in a milk bath surrounded by flowers. It's an homage to my mother who died from ALS almost two years ago, celebrating the legacy of feminine power. Another short performative film titled The Alien was put on hold prior to Covid. Three years later, I am finally ready to produce it. I am playing both characters—an alien from outer space who encounters a border guard. My grad school sculpture professor Mary Giehl created this fabulous snake alien costume made from holographic spandex material for the film. My third video tentatively titled The Bath is about a male cross-dresser struggling to come to terms with his identity. I will be behind the camera for that work. The idea came to me in a dream. I usually don't remember my dreams so vividly, but I woke up with a very detailed synopsis and shot list.

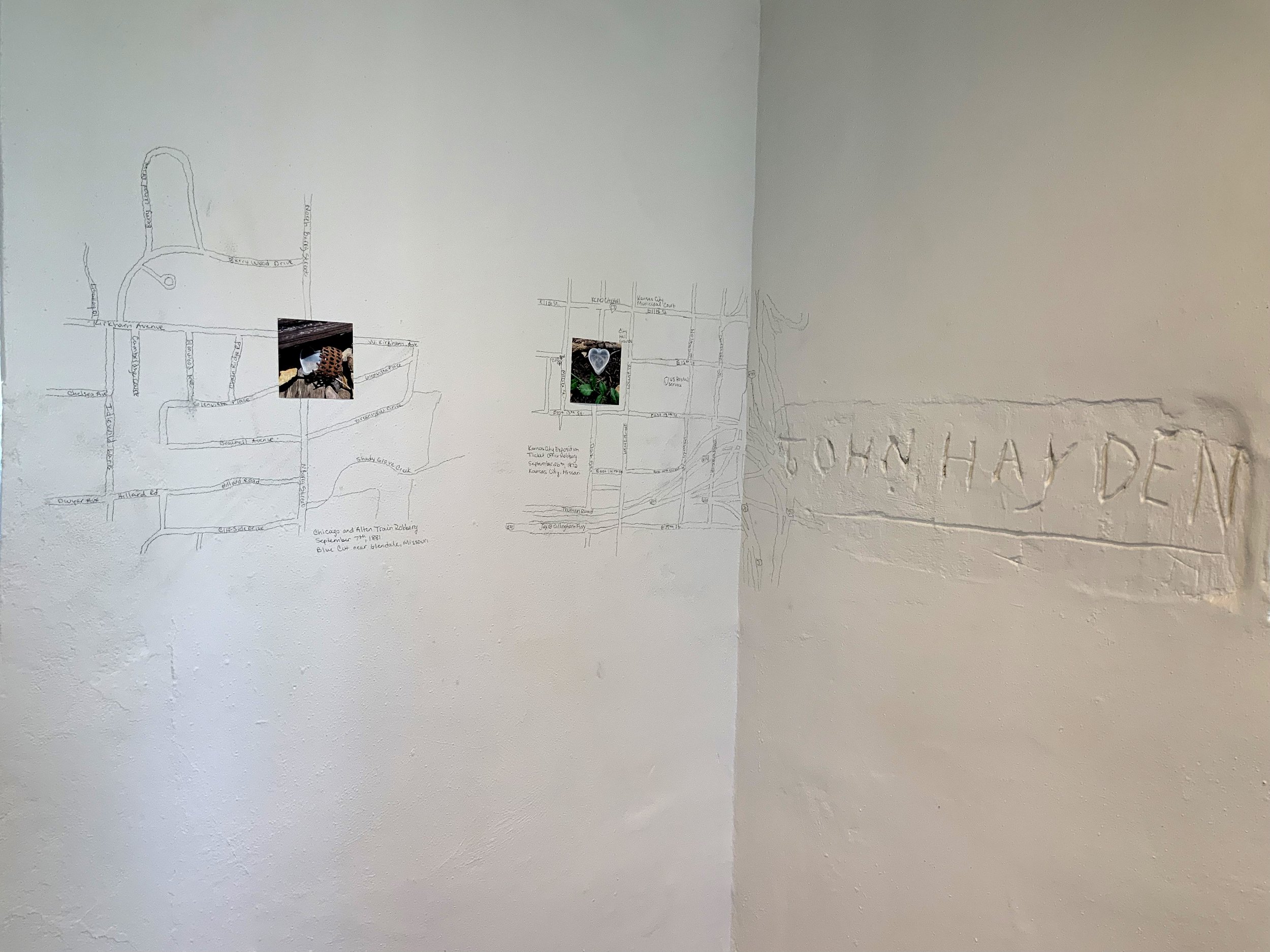

PK: In one “jail cell” or gallery of the OJAC installation you are installing a wall that contains a large map and monitors. Can you briefly explain this aspect of the installation?

CC: Over three summers, I traveled to the sites that Jesse James and his gang lived and outlawed. I filmed at each of the sites and left my DNA in the form of a lock of hair. The 22-channel video installation includes short videos from each of the robbery sites and homesteads. My quest goes beyond the personal connection of ancestral heritage to examine issues of fake news, gun violence, and criminal celebrity stardom. The project addresses the cultural mythos of criminals, specifically how the icon Jesse James was/is presented and commodified in books, films, comics and historical sites, as well as the current and problematic fascination with DNA networks such as DNA.com. Accompanying the video installation is an audio guide featuring acclaimed Dallas actor Ike Duncan, who narrates excerpts from historical newspaper accounts of the James Gang robberies. Journalist John Newman Edwards wrote articles praising Jesse James' exploits. The articles ran nationwide through Associated Press and were key in establishing the James Gang's fame. In addition, an original musical score composed by Dallin B. Peacock, inspired by spaghetti westerns—specifically the music of Ennio Morricone, plays in the background evoking the mood of the Wild West.

PK: You have also created some discrete objects in the form of prints/photographs as well. What’s the subject matter of those and how do they relate to the larger project?

CC: In the smaller jail cell, I am exhibiting a new work of images depicting the locks of hair left at each scene with a small hand drawn map of the site in the background. Growing up, my maternal grandmother's family was very divided on the topic of Jesse James. My mother's first cousin did the genealogy, so I was able to determine the exact lineage. My great-great grandmother's second husband, William James, was first cousins with Frank and Jesse James. After the divorce, all photographs of William’s were destroyed. Some family members would have preferred to keep the connection secret—it was not acceptable to air one's dirty laundry, especially a nefarious connection that could negatively impact a family's reputation or standing in the community. As I traveled, I met people who also claimed to be descendants of Jesse James. In fact, Jesse James' body was exhumed in 1995, due to a dispute over whether he faked his own death and moved to Granbury, Texas. There is a long tradition of saving hair as a keepsake of a loved one. In fact, when I was in Independence, Missouri, I visited Leila’s Hair Museum, which houses the largest collection of antique hair wreaths. I consider my hair mementos an offering to the sites as a way to make peace and reconcile with my past. Additionally, I have fun imagining what people might think when they discover them.

The 2022 Cell Series is generously supported by the McGinnis Family Fund of Communities Foundation of Texas, Kathy Webster in memory of Charles H. Webster, and the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional funding from Jay & Barbra Clack, Margaret & Jim Dudley, and Jenny & Rob Dupree.