This August’s camps looked a little different than previous summers but the OJAC Education Department had no shortage of fun planning them!

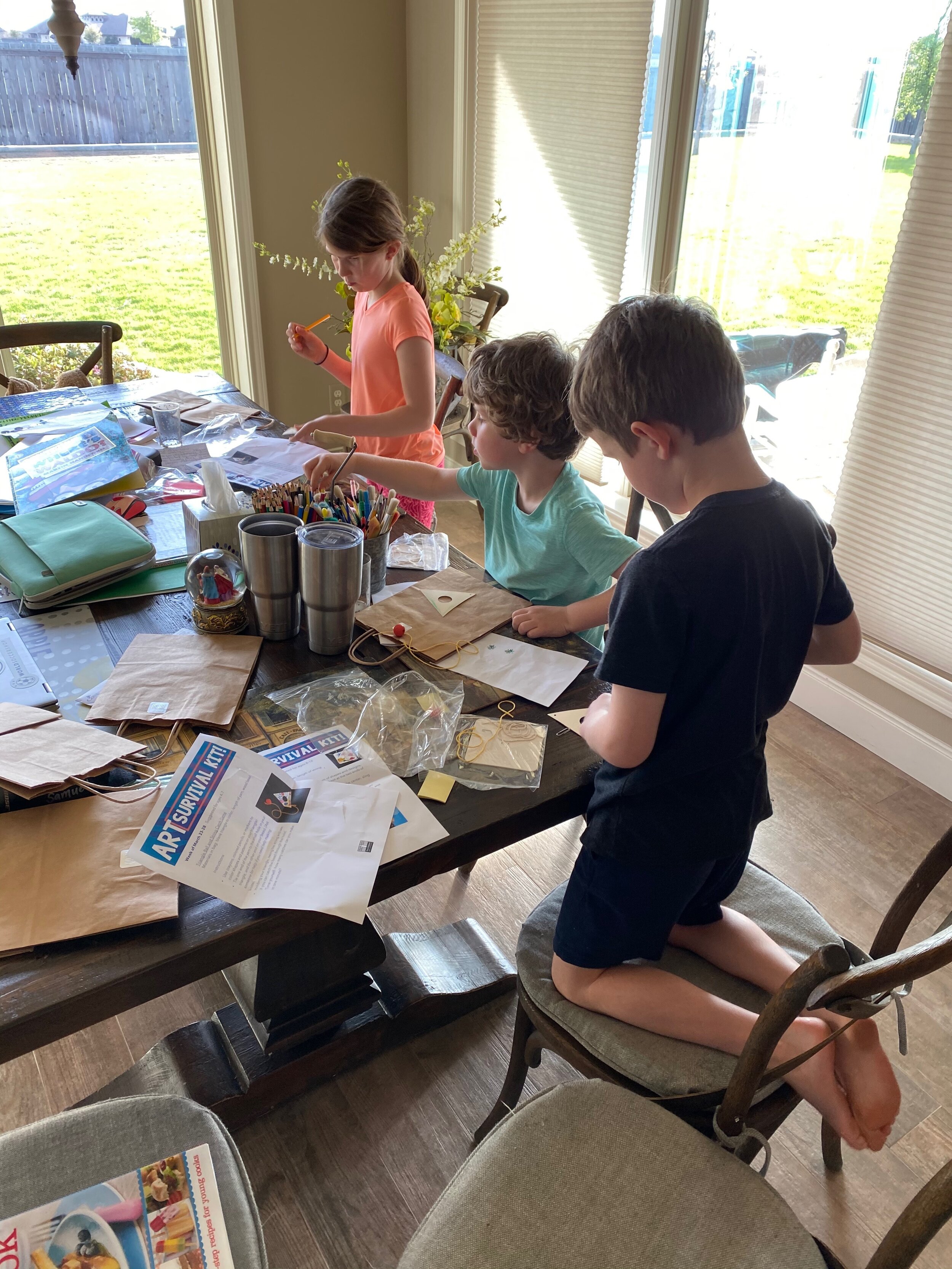

K-6th graders from all over Texas registered to participate in this years virtual art camps. (Living 6 hours away from the museum is no problem when the experience is virtual!) Each day, students opened new envelopes of supplies, snacks, and gifts while watching pre-recorded videos put together by OJAC’s education staff.

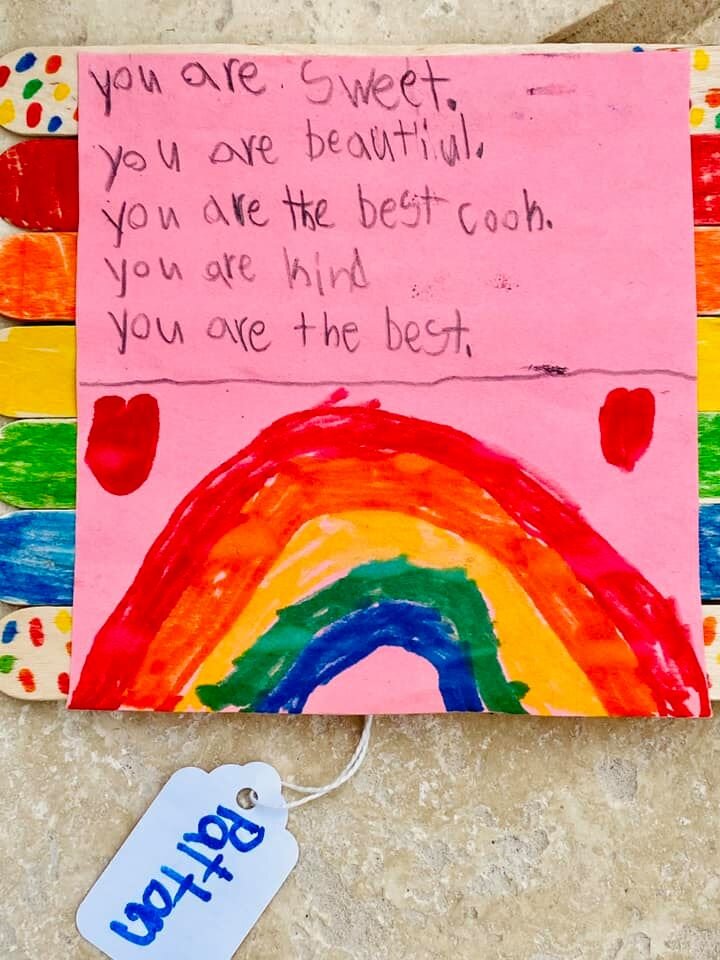

Here at the OJAC, you know we love a cultural deep dive! We take any opportunity to explore artifacts from the many countries represented in our collection- which is why our annual Cultural Connections Camp is a staff favorite! Each summer for the last 20 years, we have explored a different culture from our collection with our K-6th graders- celebrating the history, traditions and art, as well as the food, music and games of each location! This year’s focus was the Andean cultures of Peru…so we were able to investigate pre-Colombian collection artifacts from the Moche, Chimu and Inca. It’s clear from the images and feedback we’ve received that the kids loved the lessons and crafts as much as we did! (Which is quite a lot! Who wouldn’t love weaving a mini llama blanket with pompoms or a custom, tooled- metal headband?!) They enjoyed the music of mountain-top musicians, explored the terrain of the Andes and the architecture of Machu Picchu, tried their hand at Incan symbols, and watched an ancient Sun Festival!

We’ve already shipped out supplies for our Things on Strings Puppetry Camp this week (a local legend for over 30 years!) and we’re deep in preparation for Frontier Days: the Tonkawa! next week. Our local history archives are such a great resource for bringing the past to life, and our THCP Coordinator, Jewellee Kuenstler, always know how to make it fun! She can’t wait to introduce our students to the indigenous Tonkawa culture of central and north Texas with cultural crafts, music and food!

We are having a blast with this new format and feel grateful for the accessibility it has created for our programming. Check back for more images from the upcoming weeks as parents across the state share their students kitchen-table camp creations!

Molly Gore Merck, Education Coordinator